Four Foundational Questions

By Charlie Conrad

PART I: Laying the foundation – intent vs. means vs. results

Your conversations with

people and groups may be similar to mine; I hear many people express the sentiment that they no longer feel represented by either of the two major parties. They feel unmoored from the platforms, candidates, and rhetoric, adrift and uncertain in our chaotic socio-political world, without a clear course, destination, and absent a captain they trust and believe in.

Some remain simply functional party members, registered with the dominant party in

their district for the sole purpose of voting in the primaries, rarely enthusiastic about their ballot choices. Others, remain unaffiliated and disenfranchised from voting in Oregon’s closed primary system which results in the most democrat-democrat running against the most republican-republican in the general election, with 95 percent of the districts already decided by the entrenched party.

I’ve written about factionalism previously in Perspectives Issue #1, specifically the warnings from Ben Franklin in his comments after signing the Constitution and Washington’s Farewell Address (James Madison’s The Federalist #10 is also often quoted in these discussions). In this two-part article I seek to

go deeper into one area of conflict between humans, that is, between us, and how Chenele and I plan on contributing to the conversation, hopefully, providing a purpose and a destination for those feeling adrift.

First, setting the foundation, Common Ground – United We Stand is non-partisan and policy agnostic, we support system reforms which enable people to have a meaningful opportunity to have a say in who represents them, regardless

of which person or party they vote for. For this to happen, three elements are required – voters, candidates, and a system bringing them together.

My focus in this article is on us as humans, our humanity, base nature, and attributes which imbue themselves in our creations, including systems, government, and institutions. We are complex, have many sides, nuances, and are inconsistent.

Our positive and negative attributes are relative, contextual, and temporal.

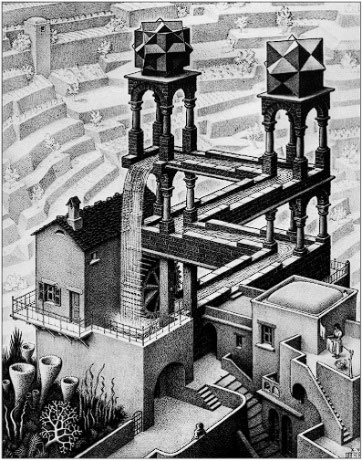

Sometimes, oftentimes, we want something to be true and work diligently to make it true. We want a perfectly efficient, perpetual waterwheel such as WC Escher’s Waterfall, to create

gold from lead, or for the tooth fairy to exist, along with countless other things – but alas, the universal laws of physics will decide what can and cannot be. But I think it is just as important to remember that the cognitive short-cuts our brains have built over eons to compensate for our limited abilities anchors our perceived reality. Physics says yes or no, while our brains say – I’ll consider it, or not.

Sometimes, oftentimes, we want something to be true and work diligently to make it true. We want a perfectly efficient, perpetual waterwheel such as WC Escher’s Waterfall, to create

gold from lead, or for the tooth fairy to exist, along with countless other things – but alas, the universal laws of physics will decide what can and cannot be. But I think it is just as important to remember that the cognitive short-cuts our brains have built over eons to compensate for our limited abilities anchors our perceived reality. Physics says yes or no, while our brains say – I’ll consider it, or not.

As an example - what color is

the dress to you? Is it blue/black? Gold/white? Who is right? Is this a zero-sum reality? If I am right, you must be wrong. We humans have difficulty admitting when we are wrong and have developed numerous psychological tricks to avoid admitting mistakes, even to ourselves. We succumb to hindsight bias, rewriting

history in our minds, misremembering certain aspects, we engage in confirmation bias, or motivated reasoning, just to name a few of the numerous biases and heuristics afflicting our decision-making process.

is right? Is this a zero-sum reality? If I am right, you must be wrong. We humans have difficulty admitting when we are wrong and have developed numerous psychological tricks to avoid admitting mistakes, even to ourselves. We succumb to hindsight bias, rewriting

history in our minds, misremembering certain aspects, we engage in confirmation bias, or motivated reasoning, just to name a few of the numerous biases and heuristics afflicting our decision-making process.

The famous Trolley Problem (there are several variations) highlights some of these – a trolley is out of control and will kill five people unless you pull a lever to divert it, killing only one, what do you do? Working through this thought

experiment gets to the core of who you are as individual – your personal ethical code and moral convictions. Does your decision change if the person you kill is pregnant, a child, or family member? What if one of the five is a rival? Does this seal the fate of the other four? Our decision making is also contingent on physiological factors such as our mood, hunger level, or if we are in a hurry, all which complicates the matter.

The Trolley

Problem illustrates a source of conflict with roots in our individual innate nature, which is the long-standing philosophical debate between ends vs. means. Do the ends justify the means? Which is more important? And how does your intent fit into the equation? Or, as Machiavelli and other political philosophers phrased it: Virtue Ethics (our individual motives) vs. deontology (means/process) vs. consequentialism (result). Intent, means, result.

Does your Trolley Problem answer change if you have to physically push someone in front of the trolley? Do you have to look them in the eye when they die? Or can you shield yourself, or do it from a distance? As Lt. Col. Dave Grossman discusses in his book On Killing, killing at a distance is easier psychologically than in hand-to-hand combat. As a side note: many of the rhetorical techniques used by demagogues such as de-humanizing and “othering” the “enemy” are discussed in his book

too.

Many moral decision-making dilemmas we face result from attempting to solve this philosophical proof – intent, means, result. In law enforcement we had a similar framework – intent, means, and opportunity. For most crimes, all three elements needed to be present and articulated for prosecution to proceed. Is that the right standard for our public policy process?

Should

we require our public policy machine to begin with a virtuous intent, followed by a logical, thoughtful process, so we might achieve a valid/legitimate outcome?

Over the past few decades, and certainly since the Constitution was adopted, our elected officials have become overwhelmingly focused on results, neglecting the means. This is evidenced by the increase in performative, click-bait, politics – the objective is simply to pander to their base,

triggering fear, anger, and disgust so they can win re-election. No single factor led to this unfortunate consequence, but social media algorithms targeting polarizing issues, enhanced party marketing, incorporating political technology, and the proliferation of super PACs (i.e., dark money) all certainly contributed.

This simple truth has led to a lack of (or near absence of) political humanists and/or statesmen holding office, or at least holding office for

more than one term. Fewer politicians focus on results benefitting people and improving their lives by providing security, stability, and opportunity, and by means which adhere to our rule-of-law based system, controlled by checks and balances, and focused on the long-term greater good.

Our bi-cameral (hierarchical) legislature was structured to balance human nature with maintaining the system. The House of Representatives was seen as being filled by

passionate, vacillating people representing the “masses” (i.e., the lower house), while the Senate was intended to focus on the system – (i.e., the upper house). A balanced public policy outcome was the anticipated result of this combination. Unfortunately, the party first mentality has tainted the results, and nefarious intents have corrupted the means. But, with hard work amongst people embracing cooperation, collaboration, and compromise – we can get back on track, particularly in state

legislatures, which function as policy laboratories and are the proving grounds for national politicians. People, country, party – in that order.

This is a good place to stop if you are short on time or simply want to ruminate on the dynamic between intent-means-result, and how balancing them impacts political discourse. The following section builds on this conflict and then boils the discussion down into four questions and how Chenele and I are seeking to

answer them.

PART II: Building upon the foundation i.e., progress

Picking up the discussion regarding intent-means-results and how this looks in our public policy process.

The current immigration discussion is a prescient example. Under the Virtue Ethics rubric Trump and his administration continually state they are exporting “bad and truly

evil criminals” – which triggers our core personal ethics code to “combat evil” and protect the innocent. Virtuous right? Courage to protect the innocent and compassion for those in need. But some of the opposition messaging focuses on virtues too, the human side of the deported immigrant. Including their flight from persecution, desire for a better life, the fact they haven’t committed any crimes, they are a father, husband, employed etc. There is an inherent conflict between these two

viewpoints. Is the dress blue/black, or white/gold? Or both? Virtues are relative and contextual.

The means/process component is a point of conflict and friction too. The process by which the administration is deporting people absent due process, with a few highly notable mistakes, and seemingly little initiative or interest to correct some of the mistakes, raises the hackles of folks where process, particularly public processes and adherence to the rule of law

is a core belief. Yet those who believe that as long as the ends (getting rid of evil doers or potential evil doers) is achieved, the means are irrelevant, because after all “they” aren’t citizens (although many are in the United States legally).

Some of the opposition isn’t necessarily opposed to the result, they oppose the process and the absence of adhering to the rule-of-law. A February 2025 Pew survey found 59 percent of U.S. adults approve of increasing deportations. But in an April 2025 Washington Post – ABC News – Ipsos poll, 46 percent of U.S. adults approve of the way Trump is handling immigration, down from 50 percent in February.

The inherent conflicts between the motives, process, and results highlight the innate complexity that resides within all of us, and subsequently the institutions we create, use, and manage.

With

that in mind, let me tell you where I am at right now in observing our present socio-political world. Amidst all the chaos I seek a toehold, something to ground us, something we can all revert to, to reaffirm our shared purpose. To that end, I’ve broken things down using the first principles approach to four fundamental questions.

Question #1 is the cornerstone: Do all humans have the same rights when they are born?

This question starts at the beginning with a common experience we all share - birth. Historically in many societies, for girls and anyone who is different – the answer has been no. Is that who we are as Americans today? We know where oppression leads – misery, pain, vigilante justice, treating others as inferior, or as property, the denial of basic human dignity, and exploitation.

Is that the world we want our descendants to be born

into without knowing if they may be “different”?

Question #2: Can we agree on our fundamental human nature?

I think we, as a nation, have lost sight of a basic, shared, bedrock understanding of us as humans. Here are five aspects of our humanness I believe we should seek agreement on and acknowledge:

1. We are passionate

first, reasoning second. In behavioral economics terms, this is the dynamic between System 1 and System 2.

2. We are hierarchical – always looking to be better than someone else.

3. We are social – we want to belong and be part of a community with shared beliefs.

4. We are self-motivated – always seeking to advance our interests over that of others.

5. And finally, we are fallible – we all make mistakes, as

do the entities, systems, and institutions we create.

In short, the cynical view of humans is that we are passionate, elitist, factional, self-motivated, and make mistakes.

But, can we all agree on our fundamental nature – appreciating and capitalizing on the upside while acknowledging and mitigating the downside?

Question #3: What is the essential purpose of

government?

I see the government’s principal purpose as managing interactions/conflicts between humans. Thomas Hobbes resonates with me – we all are born with the same rights and exercising those rights puts us in a constant state of war. The natural solution therefore is to compromise and cooperate so that we each respect each other’s rights, and we are therefore both better off.

Can we agree on the essential purpose of government?

Question #4 brings all these together: What do we want our government to do?

Think of the principle “form follows function” - is government only for common defense and enforcing the rule-of-law? Do we want a social safety net, manage the economy, provide affordable and accessible healthcare, promote infrastructure, stabilize international trade, or something else?

As I see

it, until we can agree on the answers to these questions, we will never agree on the policy process, let alone the policies themselves.

Getting back to the questions I want to answer – if you agree we all have the same rights, including the right to be meaningfully involved in the public policy process and administration of the government, that our passions preempt our reasoning, if we and the things we create are imperfect, if a core function of the government

is to enforce the rule-of-law – then help us create a system and institutions to protect us from us. That is my ultimate goal – to use Nassim Talib’s term – we need to become antifragile. How do we become stronger because of the stresses being placed upon our system? How do we go forward with the knowledge and understanding we have gained? How do we maximize this experience so those that are yet to come have opportunities, stability, and rights?

An aggravating

factor in the intent – means – result conflict is that many “results only” supporters see the world as a zero-sum game. For me to win, you have to lose. For my party to win, yours has to lose. Zero-sum politics does not allow for a thoughtful, deliberate, participatory process – it is an incumbrance to be avoided.

The mindset at the radical, yet, unfortunately real, end of the spectrum - I will destroy you on my way to winning. Can you see the dark side of our

raw human traits embedded in this mindset? The passionate pursuit of a result which advances the group’s self-interest to the determent of others, absent a process which might force them to face their own fallibility. If I am right, how can I be wrong? And, I am right – so you must be wrong. Obstinate hubris.

The Second Law of Thermodynamics states that the natural direction of the universe is towards entropy, that is randomness or decay. Entropy applies to our

natural and built physical world as well as our contrived human systems. Maintaining, repairing, and replacing systems require energy – our energy. 250 years in, I think this is the time to apply concentrated, concerted energy to modernize our socio-political system by using our combined knowledge, experience, and abilities to guide the construction. We don’t need to overhaul the system, but we certainly have some cracks and worn spots needing attention.

My

goal is to contribute to this modernization effort, to enable it to protect us from us. But first, we must acknowledge and accept who we are as humans and agree on the rules governing our interactions. The foundation work comes first. Only then can we establish a socio-political system capable of withstanding repeated attacks which can persevere over time.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t leave you with the Four Cardinal Virtues of the Stoics – Wisdom, Temperance,

Fortitude, Justice. Hopefully, reflecting on these will fuel your passion to contribute, provide the impetus to plan, steel your back when courage is needed to do the right thing, and enable you to treat people justly with grace, compassion, and understanding. A reasoned life dedicated to public service is a good life – at least it has been for me.

Let me see if I can concisely sum up my thoughts based on my observations. We are human, we are complex, our

systems are complex, we have de minis control over events, but we can decide to cooperate, compromise, and collaborate to the benefit of all, or not.

With that, Chenele and I will be hosting salons on Interintellect to discuss and work through these four questions. We welcome anyone who wants to join us as we

start working towards arriving at a final destination, one that balances us as humans and the systems we create to govern us. We anticipate our first discussion will be in early June and will send a link once we finalize the date and time.